How to write history collectively: History made simple

If you wish to write history collectively, then you are at right spot. When it comes history, to write is challenging. Your decision to write must be well-planned. We are here to help you in planning.

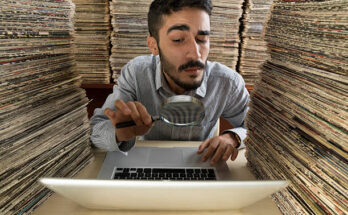

A better start: write history

IMAGE CREDITS: Unsplash.com

Skip the arrogant, dull beginnings. Don’t begin your essay with something like, People from all cultures have engaged in numerous, protracted disputes over a variety of political and diplomatic matters throughout recorded human history, which has piqued historians’ curiosity and led to the development of several historical theories. Suppose you’re writing a paper about, say, how the British handled the 1857 insurrection in India. This is total dreck, it bores the reader, and it shows that you have nothing worthwhile to say. Bring it home quickly.

Better to begin with: The 1857 uprising forced the British to reconsider how they ran their Indian colony. This line clarifies for the reader what the topic of your paper is and makes it possible for you to present your thesis in the remaining sentences of the introduction. You might continue by saying, for instance, that it was disingenuous of the British to show more sensitivity to Indian customs.

A convincing thesis: write history

You must have a thesis, whether you are writing a senior thesis or an exam essay. Do not simply redo the assignment or begin summarizing your knowledge of the subject. Think to yourself, “What exactly am I trying to prove?” Your thesis includes your position on the matter, your point of view, and your defence. Despite being true, the factual statement “Famine struck Ireland in the 1840s” is not a thesis. The argument is that “The English were responsible for the famine in Ireland in the 1840s”; whether or not it is tenable depends on the context.

A strong thesis responds to a crucial issue regarding how or why something occurred. Who was accountable for the 1840s famine in Ireland? Once you’ve typed down your thesis, don’t forget about it. logically from paragraph to paragraph as you develop your point. Your argument should always be clear to the reader as to its origin, progress, and conclusion.

Analyzation is must

IMAGE CREDITS: Unsplash.com

Students frequently wonder why their lecturers penalize them for merely narrating or summarizing rather than engaging in in-depth analysis. What does the word “analyse” mean? To analyse means to divide anything into its component pieces and to research how those component parts interact. Hydrogen and oxygen can be separated out of water through analysis. Historical analysis, in a larger sense, examines the causes and import of events.

The goal of historical analysis is to uncover connections or differences that are not immediately apparent. Historical analysis is important because it assesses sources, gives causes importance, and examines conflicting theories.

However, you might consider summary and analysis in the following manner: The elements of a summary are who, what, when, and where; the elements of an analysis are how, why, and how it will affect. Many students believe that in order to prove to their professors that they are knowledgeable of the material, they must first provide a lengthy overview. Instead, make an effort to start your analysis as soon as you can, often without any sort of summary.

The facts will “shine through” in a sound analysis.

Critical usage of evidence: write history

Historians evaluate their sources critically and double-check them for accuracy, just like skilled detectives. You wouldn’t think highly of an investigator if they simply used the adversary of a suspect to verify an alibi. Similarly, you wouldn’t be too impressed with a historian who attributed all of World War I’s causes to the French. Consider the two arguments below regarding the causes of World War I: 1) “Germany is to blame for the 1914 calamity.

You need to conduct some investigation because they cannot both be correct. The greatest strategy is to always inquire: Who wrote the source? Why? When? under what conditions? who for?

Be precise and straightforward

IMAGE CREDITS: Unsplash.com

Vacuous claims and broad generalizations imply that you haven’t taken the time to learn the subject. Take a look at these two phrases: “The people overthrew the government during the French Revolution. The Revolution is significant because it demonstrates the necessity for independence among people. Who are they? Unemployed peasants? urban squatters? wealthy attorneys? what authority? How, when? Who precisely need freedom, and what did they interpret freedom to mean? A clearer description of the French Revolution is as follows:

The Parisian sans-culottes pushed the Convention to implement price controls in 1793 as a result of the threat of rising prices and food shortages. Although this assertion is more constrained than the grandiose generalizations about the Revolution, it differs from them in that it has the potential to lead to a thorough examination of the Revolution.

Be careful about chronology: write history

Establish a clear chronological structure for your thesis and avoid making illogical transitions. Be careful to avoid date ambiguity and anachronisms. If you write, “Napoleon abandoned his Grand Army in Russia and caught the redeye back to Paris,” the error is clear. The issue becomes more subtly evident if you write, “Despite the Watergate scandal, Nixon easily won re-election in 1972,” but it’s still a serious one. (The scandal wasn’t made public until following the election.)

Your lecturer might think you haven’t researched if you write, “The Chinese revolution finally succeeded in the twentieth century.” the revolution? When did the 20th century begin? Keep in mind that history is built on chronology.

Citations and referencing is important: write history

IMAGE CREDITS: Unsplash.com

In a brief paper with one or two sources, your professor could use parenthetical citations, but you should utilize footnotes for any research work on history. Parenthetical citations are ugly; they mar the text and disrupt the reading process. Even worse, they fall woefully short of capturing the depth of historical sources. With good reason, historians are proud of the enormous variety of their sources.

Parenthetical citations like (Jones 1994) may be appropriate for the bulk of social sciences and humanities fields where the source base is often limited to recent English-language books and articles. But historians need the versatility of a complete footnote.